Please scroll down

Isocèle

by Elisabeth Jobin

A collection of stemmed glasses are placed on the floor, upright and intact, or even broken, lying next to their debris. Pushed up against the wall in a random cluster, these champagne flutes in all of their simplicity compose the first piece in the exhibition Isocèle presented by John M Armleder at Rectangle. Entitled Charivari, this work occupies the floor of the Brussels artist-run space which, for this project, will remain closed to all but virtual visits. Thus, by the time visitors of this viewing-room see the images of the work on their screens, the work may no longer exist, it may no longer be physically in the space, having already been cleaned up and put away. It essentially exists there only by assumption. “Everything is a variant of something else,” Armleder explains. A supposed work is a variant of a real work. An exhibition room is a variant of a mental space. A broken glass a variant of an intact glass.

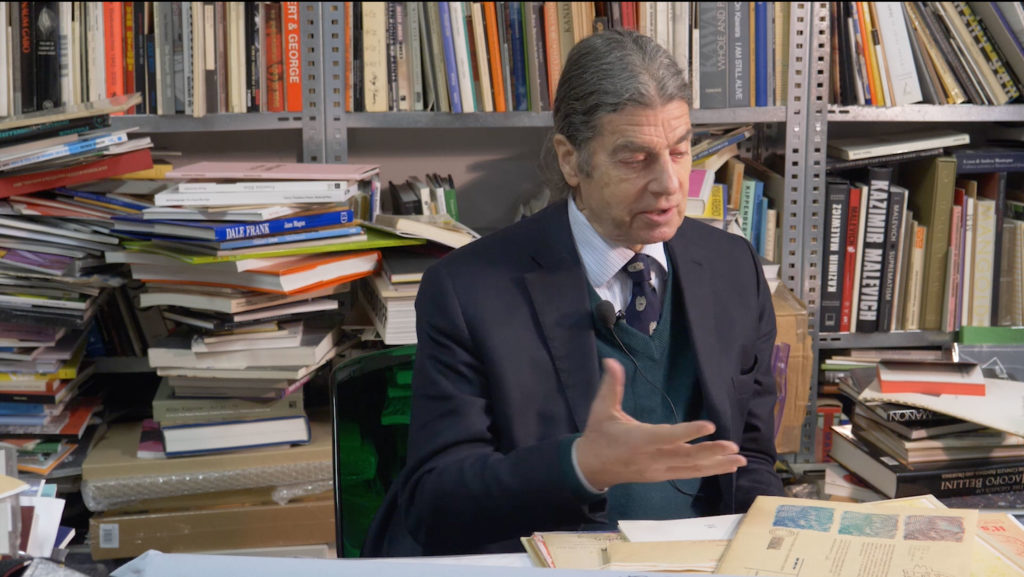

“It's a bit of a flashback”

— John M Armleder

As such, Rectangle, an art space founded in Brussels in 2012, could present itself as a variant of Ecart, the alternative art space co-founded by John M Armleder with friends Patrick Lucchini and Claude Rychner in Geneva in 1969. Like Rectangle’s virtual space, the one occupied by the Ecart group when it was founded 50 years ago in the cellars of the luxurious Geneva Hôtel Richemond, was “non-consecrated”– that is to say that the primary function of these spaces was not to host artistic proposals. “It’s a bit of a flashback,” admits Armleder, who notes the proximity of the exhibition conditions of Ecart and Rectangle despite the time-lag. Rectangle’s viewing-room thus seems the perfect place to exhibit a piece whose title, Charivari, has a slightly old-fashioned, almost nostalgic resonance. All the more so since the term means a “discordant and tumultuous noise” or better yet a “great collective noise.” A word that calls for the number, the group – whether it is the one at the origin of Ecart or of Rectangle.

a “great collective noise”

Charivari is a word that refers to an action, an event, a regrouping, and that retains in itself the memory of a shared accident. Similarly, the intact stemmed glasses of Armleder’s artwork summon celebration, and the broken glasses summon the incident. However, neither the cause nor the story at origin of the festivity or the catastrophe, nor, for that matter, is the catastrophe itself explained here. The piece is proposed as the result of a mysterious combination of circumstances, or as an evaluation caused by a series of unknown events. And yet, the accident at the origin of Charivari has already repeated itself several times. The work was created in 2015 on the occasion of John M Armleder’s exhibition of the same name at the gallery Massimo De Carlo in Milan. It was placed next to a door between two rooms of the gallery where it almost went unnoticed. Three years later in 2018, Armleder reactivated the piece with other glasses – he always instructs the team of the space to purchase them, without any preference of form or quality– in an exhibition at MUSEION, the museum of modern and contemporary art in Bolzano. The work integrated itself into the centre of a large installation with yet again the same discreteness. Rectangle presents the third version of this artwork, opting, this time, for champagne flutes. Here, Charivari is exhibited with just another installation, Copacabana (2020), and is accompanied by an edition in two boxes produced by Rectangle: Rivachari (a box containing an intact champagne flute) and Varichari (a box containing a broken champagne flute).

“All creation is a repetition of something that already exists”

— John M Armleder

Resume, redo, replay, reactivate, reuse. Repetition is part of Armleder’s practice. He considers it as commonplace. “All creation is a repetition of something that already exists,” he explains with a hint of amused fatalism. The same goes for Charivari that can be replayed over and over again. “Absolute newness does not exist,” he continues. It may not even be desirable. What is the point of it, really? Because through remakes, “repetition itself becomes unprecedented.” Back, then, to square one. Stemmed glasses travel, with the same indifference from the dining room sideboard to the glossy floor of a gallery showroom, a museum or an artist-run space such as Rectangle. Only the nature of the exhibition space changes, and with it the way the room is viewed. “Permanence is an illusion,” Armleder concludes, being sure to invalidate the assertions and verdicts stated above.

And what more? “There may be something of a childhood memory,” he admits. He grew up in a large hotel in Geneva – the Hôtel Richemond, to be precise – and attended parties there of which he remembers one image in particular: when, at the end of a ball, the servers would hurriedly push in and pile up chairs in the corner of the large room before cleaning it. It was a kind of “false tidying up,” he explains. The furniture was gathered and grouped together in an unsystematic way evoking through its clutter that “something that had happened” without anyone knowing exactly what. This image conveyed an undefinable feeling that was actually much more striking than the actual course of the party itself.

The same goes for Charivari, an artwork that remains frozen in an image of the following or the foregoing without ever revealing the scenario. It is true that Armleder has a particular affection for the in-between, the intermediary, the behind-the-scenes, the scaffolding, which are both “just before” and “just after” – knowing before or after what exactly has no significance in the end. From this perspective, Charivari is part of the work that the artist has been carrying out since the 1990s on decors, these copies of the real whose factitious facture is visible at first sight, but which everyone accepts to be true according to a collective agreement in order to better taste the anticipated pleasure of the story that this “true fake” is about to welcome.

references ranging from dreamy exoticism to the remaining reliefs of a supposed party

The relationship with decors is even more striking in Copacabana, a piece presented for the first time at Rectangle. Here, the stemmed glasses are deposited on a pile of dirt next to stones and books related to gold and the codes of luxury – yet another reference to the Hôtel Richemond and the use of gold in the work of Armleder. A houseplant surmounts all: it is about a plant often qualified as “exotic,” for lack of a better term, those which one buys in supermarkets to pleasantly fill the empty space between two pieces of furniture of the living room. So much so that it ends up melting into the decor and turning into ornamentation. It thus discreetly transposes an outdated, Western and nostalgic idea of an “elsewhere” where the climate would always be clement, of an “exoticism” that never existed except in old colonial dreams into the domestic space. At Rectangle, the houseplant becomes the somewhat kitschy ornament of an assemblage of objects that have been diverted from their original context. Books, dirt, plants, glasses: all coming from different registers, they are brought together in a fortuitous way over the course of the installation, sweeping a panorama of references ranging from dreamy exoticism to the remaining reliefs of a supposed party. To complete the whole, soft music is added to the background appropriating the codes of “furniture music,” according to the formula of composer Erik Satie, a major reference of Armleder’s work. Composed by his son Stéphane, the melody imagined for this viewing-room creates a comfortable atmosphere without ever being distinguished in any way – like elevator music whose sole purpose would be to furnish awkward silences.

A final image, to conclude: that of the installation titled Un Jardin d’Hiver (“A Winter Garden”) that Marcel Broodthaers created in 1974 as part of his “Décors” series. By integrating houseplants, among other things, in a scene where he played with the codes of 19th century museology and bourgeoisie, the Belgian artist, with finesse and humour, addressed the way cultural institutions codify artistic practices and discourses. At the same time, a vast operation of demystification was being played in Un Jardin d’Hiver, as soon as the status of a work of art was adjacent to the one of a houseplant. Isn’t the decorative purpose of these two objects similar? Broodthaers’s installations are clearly not foreign to Armleder’s work. The exotic plant in Copacabana could even be seen as a tribute to its predecessor in the context of this exhibition in Belgium. A way of reminding, perhaps, that everything is a variant of something else.

« Rien ne se perd, rien ne se crée : tout se transforme »

Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier (1743-1794)

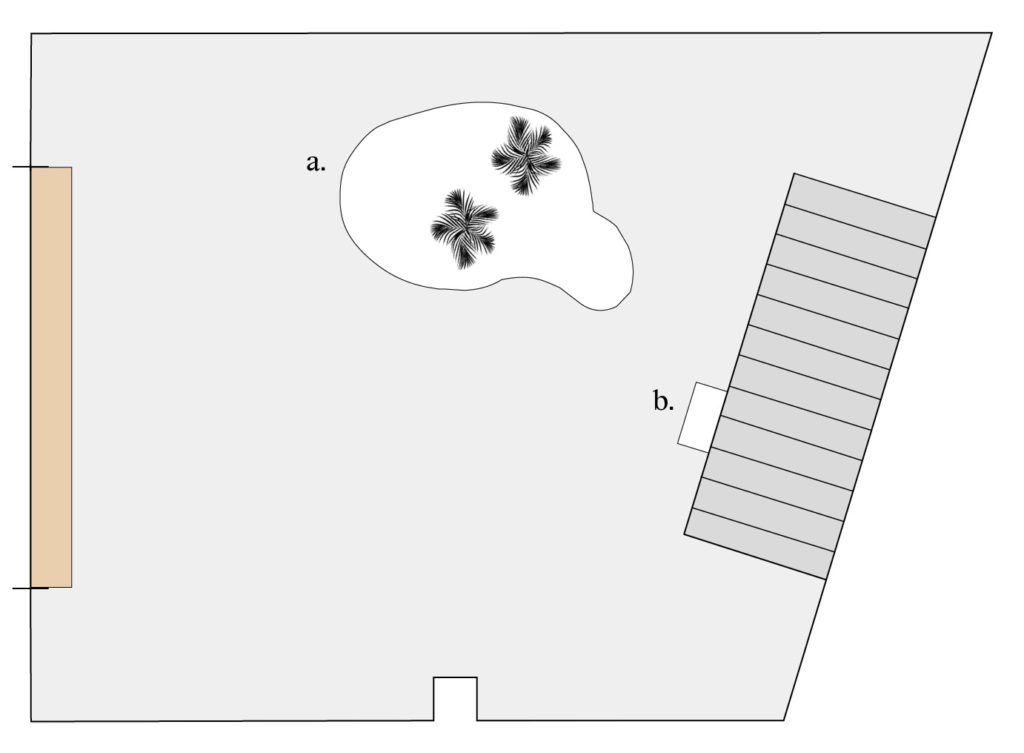

Floor Map

a. John M Armleder

Copacabana, 2020

Installation

Clear glasses, soil, plants, rocks, glitter, books

Variable dimensions

b. John M Armleder

Charivari, 2015

Installation

Clear glasses

Variable dimensions

* Stéphane Armleder (WRWTFWW Records)

Music for Beach Elevators, 2020

Tracklisting

Biography

John M Armleder

Born in 1948, Switzerland.

Lives and works in New York and Geneva.

Co-founder of the Ecart Group (1969) and closely affiliated with the Fluxus movement, visual artist John M Armleder has since the end of the 1960’s created a polymorphic body of work which encompasses performance, drawings, sculptures and paintings. Generally characterized by a sense of deep interconnectedness between life and art, and the appropriation of objects and quotes, his work is loaded with a set of influences and references which elude the modernist vernacular as well as any form of classification. Armleder gained international recognition with his Furniture Sculpture series from 1979, bringing together iconic examples of design and paintings to reflect on the trivialization of the artwork as an ornamental accessory. The artist is also recognized for his celebrated series of Pour and Puddle Paintings. “These works, born from his admiration for Larry Poons, and in accord with Armleder’s larger practice, do not hide the strategy of their fabrication nor the significance of their own process: conjuring a time liberated from formal constraints, moral obligations, and the conventions of taste and style.” (Extract from Stephanie Moisdon, ‘La Bruche du Haricot’, Almine Rech Gallery, Brussels, 2015).

Massimo De Carlo Gallery

John M Armleder

Charivari, 2015

Variable dimensions

Unique

Curated by Rectangle

With the support of

Music: Stéphane Armleder (WRWTFWW Records)

Text: Elisabeth Jobin

Translation: Katia Porro

Special thanks to John M Armleder, Lena Guevry, Stéphane Armleder, Elisabeth Jobin, Katia Porro, Pierre Buyssens, Yann Chateigné and Kanal – Centre Pompidou.