Please scroll down

Beyond the Reef

by Laila Melchior

For the last five years, Hadassah Emmerich has been developing a painting technique in which she imprints vinyl cut-outs colored in hued palettes onto canvas, paper or directly to the surface of a wall. Her compositions allude, suggest and often straightforwardly depict the feminine body in rhythmic, machinic, metallic, fractionated ways. Systematically exploring the topic of exoticism through an investigation of colors and shades, her work sets in motion specific entanglements of the exotic. Looking at it, one gets confronted with a particular take on the economy of desire, in which the notion of fetishism smoothly flows from the realm of sexuality to that of the commodity.

For the third iteration of Rectangle’s Online Viewing Room, Emmerich articulates her research and personal experience in a novel, expanded and performative manner. The artist presents new works, borrowing the exhibition title from an old song from the ’40s to outline exotified projections drawn from her coming-of-age experiences as a teenager of partial Eurasian descent living in the southern Dutch province of Limburg.

[...] on the economy of desire, the notion of fetishism smoothly flows from the realm of sexuality to that of the commodity

Marked by the lingering notes of a steel pedal guitar, the reference to Beyond the Reef immediately settles a Hawaiian mood to the show. The suggestion of a foreign taste is very much in line with what Emmerich recalls having firstly experienced at a local pasar malam, a type of night market traditionally organized by the Indo communities in the Netherlands. “My parents divorced when I was six. I stayed living with my mother and would stay over at my father’s and my Indonesian grandmother only two weekends per month”. As her notions of the Dutch and the Indonesian worlds got completely split, Emmerich’s opportunities to get acquainted with the latter were significantly reduced. Fairs such as the pasar malam became immersion bubbles, temporary events introducing her to multiple tactile, sensuous stimuli. Providing an endless offer of products, food and presentations from communities that were distant in space and about which she knew nothing or very little, the fairs introduced her to a new world. It also turned out to be a way out from the daily banality of school in a time when there was no critical discourse about the Dutch East Indies’ colonial history. Amid such sensorily charged experiences, a Hawaiian-style dance performance fascinated Emmerich in an outburst of exoticism.

“It was a bit queeny, a bit dodgy. We would rehearse listening to cassette tapes in the living room of our manager's house. Only when I moved to London for my Masters, I discovered that we were totally appropriating the dance, inventing an entirely bastardized version of it.”

—Hadassah Emmerich

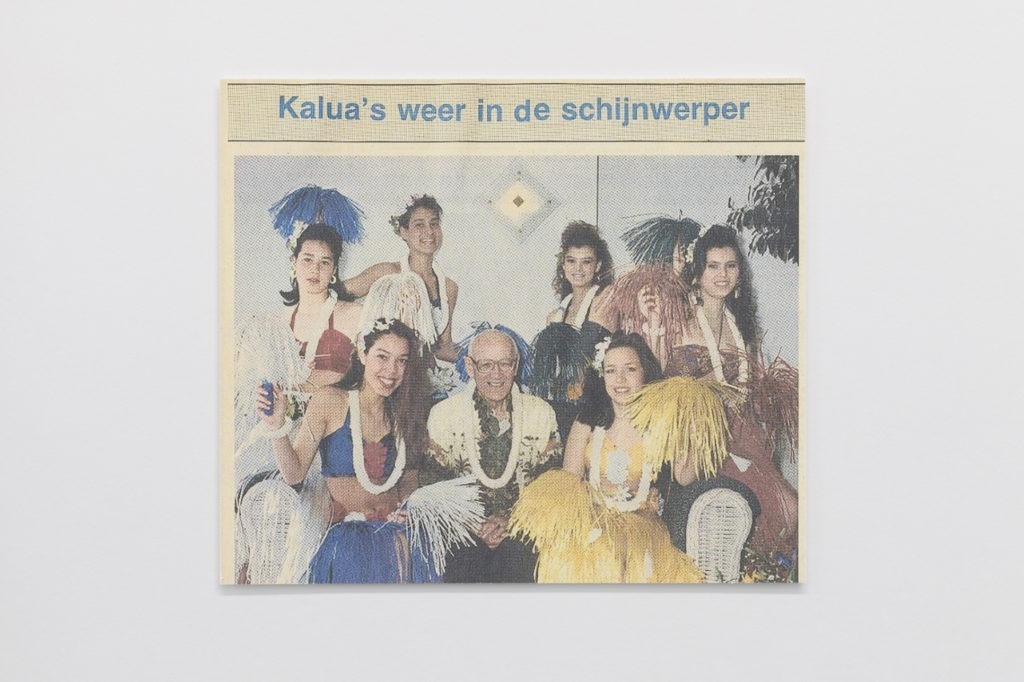

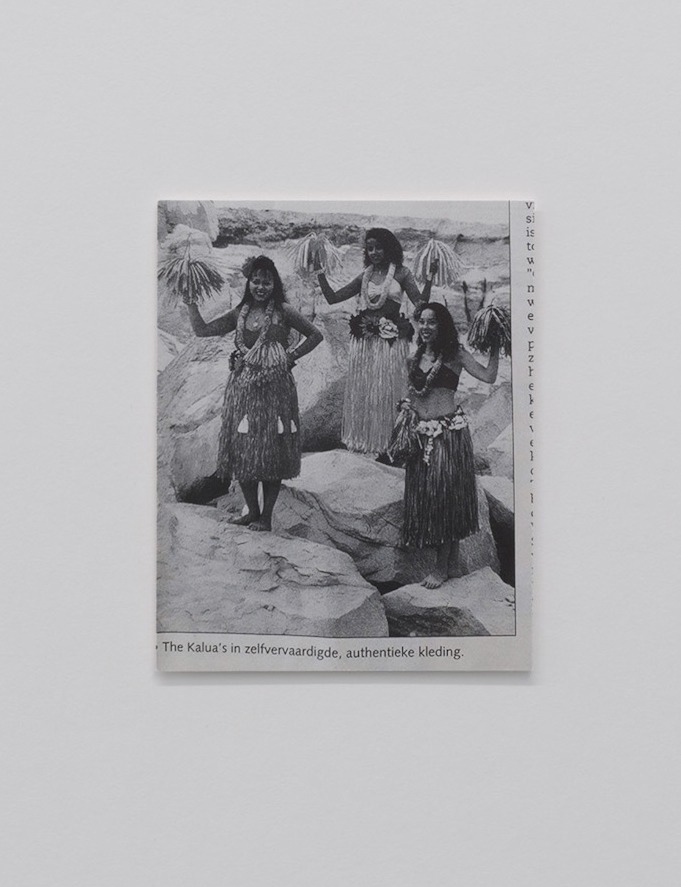

Two reproductions of local newspaper clippings highlight the Kaluas, a hula group in which Emmerich participated over an approximate period of 10 years. A photograph of the late ’90s shows the artist at a young age together with some of her colleagues. Proudly dressed in their costumes, they sit around an elderly man. Another picture, taken in a yellow sandstone quarry alongside the road near the city of Heerlen, captions the dancers in their “self-crafted, authentic clothing”. Emmerich recalls it started very innocently: “it was a bit queeny, a bit dodgy. We would rehearse listening to cassette tapes in the living room of our manager’s house. Only when I moved to London for my Masters, I discovered that we were totally appropriating the dance, inventing an entirely bastardized version of it.”

Shown for the first time at Rectangle’s Online Viewing Room, a video piece from 2004 tackles some questions around the issues of authenticity, appropriation and exotification that started to arise from that point. Emmerich performs to the camera wearing a ribbon skirt and a wreath of flowers while emulating the hula moves. Set indoors, the scene takes place against the bright greyish backlight of a typical British council-flat window. Her outfit rustles to the wind of a fan as she sways. The sound of the steel pedal guitar overlaps with her humming the tragically-hopeful tale of longing narrated in “There is a Light that Never Goes Out” by The Smiths.

A new painting made especially for the show departs from hair as a motif, enlarging the scope of Emmerich’s scrutiny on feminine forms. Already investigated in her “Cold Shoulder” series as formal and conceptual research triggered by a line of hair dye products commercialized in Curaçao, it appears here in slight movement, as if animated by the trade winds, or by the artificial blows of the fan in the 2004 video piece. Painted as an ornament on top of the hair-lock, a flower pops up as a possible entry point to the composition.

The zone located past the reef barrier [...] as a kind of unprotected territory, where freedom or menace may release or haunt a former couple’s dreams.

Familiar to Emmerich’s strategies, the overlapping notions of appeal, artificiality and exotification point to the universe of trade. Substituting the billboard traditionally proposed by Rectangle in Brussels in a digital version, a detail of the flower hairpin is currently sponsored on Instagram. The digital billboard stands in a threshold between advertisement and a tweaked additional space for an online exhibition – maybe an unusual choice for the pre-Covid era, which now opens up as a new experimental field. Targeted at audiences around the world who can click to experience an authentically fake fantasy, this projection screen stands as the typical offer of a night market, but also of the fairs that just quite recently proliferated all over the art world.

Another set of new works hangs from a bamboo stick. These works on paper present fragmented feminine bodies that become indistinguishable from the original photographs of flowers and plants from an old botanical book over which they were painted. The works expand the artist’s investigation of images as erogenous zones, insofar as foreground and background mingle beyond its figurative markers.

A sense of longing and displacement adds a bittersweet note to the show. While the original lyrics of Beyond the Reef moan about a woman who is now gone, the zone located past the reef barrier is described as a kind of unprotected territory, where freedom or menace may release or haunt a former couple’s dreams. This discrepancy between the desire to elope, enacted by the woman, and the hopes of return by her abandoned singing lover evoke multiple questions about an economy of desire, which gets complicated in Emmerich’s visual approach. Not only it speaks of bodily yearnings. It also tells us about intricate cravings for new horizons, of ambiguous relations to nature, the wish to colonize, and, more generally, about different ways we see, describe, interpret and experience inevitable clashes over radical otherness.

As a last presence marking the interwoven layers of time and space that Haddasah Emmerich proposes on Beyond the Reef, the curling ribbon skirt used in the video piece is presented in the beginning and by the end of the Viewing Room scrolling. Metallic and mysteriously industrialized, the piece remains under a strange ethnographic status: a souvenir of a bastardized world past the reef barrier where complex mixtures fuse the figures and the grounds in much fresh, sensuous ways.

“I experienced a genuine pleasure from performing as an 'exotic' dancer”

— Hadassah Emmerich

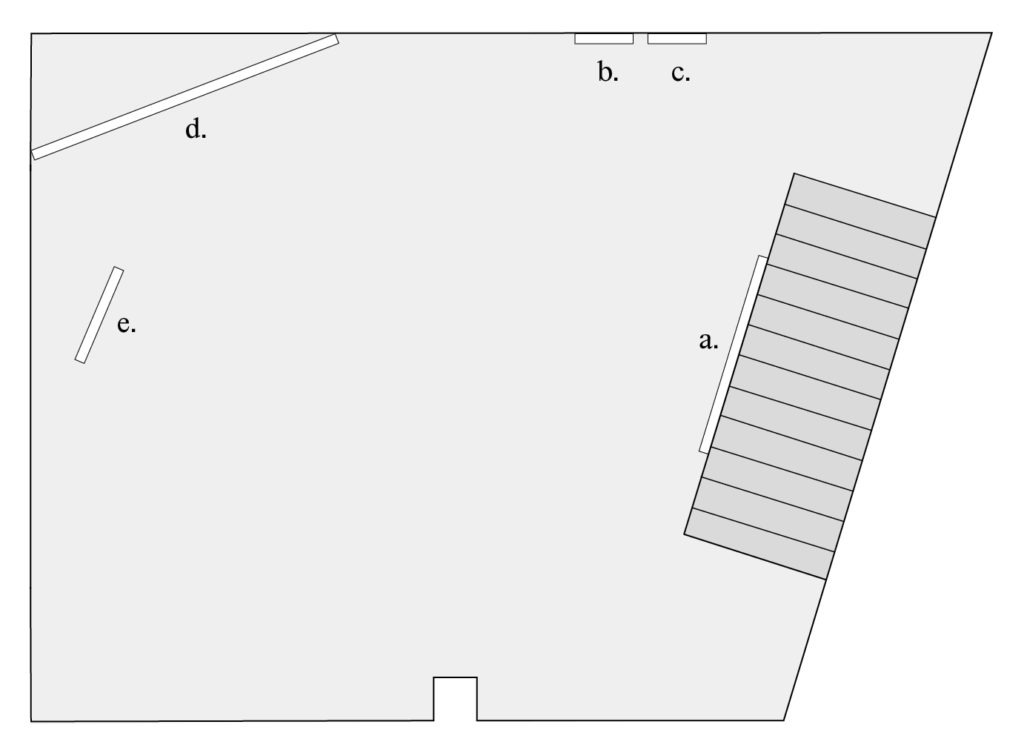

Floor map

a. Substitutionary Seduction, 2021

Oil on linen, 130 × 185 cm

b. Kalua’s weer in de schijnwerper, 2021

Print, 40 × 53 cm (framed)

c. The Kalua’s in zelfvervaardigde, authentieke kleding (1999), 2021

Print, 40 × 53 cm (framed)

d. Cold Fusion series, 2020

Oil on paper, 35 × 26,5 cm (each)

e. There is a light that never goes out, 2004

Video, 4’24”

Biography

Hadassah Emmerich

Born in 1974, Netherlands.

Lives and works in Brussels.

Body and identity, the sensory and the sensual, the commodification of the erotic and the exotic: these are frequently recurring themes in Hadassah Emmerich’s work. The sensuality of her painting resides not only on the surface of the (erotic) image but also in her refined use of colour and technical execution. Since 2016, Emmerich has worked with a new painting technique, using stencils cut from vinyl flooring, which she covers with ink and then impresses onto canvas, paper or a wall. Referring to the visual language of advertising and Pop art, she creates images that both aestheticise and problematize the female body. She depicts the paradox of simultaneous attraction and repulsion, intimacy and cool detachment, seduction and critique. In this way, Emmerich succeeds in making the act of looking truly provocative. (Nina Folkersma)

Archive

Curated by Rectangle

With the support of

Special thanks to Hadassah Emmerich, Laila Melchior, Flanders State of the Art, and the Mondriaan Fund.